Daily fantasy sports often get discussed as if they differ only in scoring rules and roster sizes. That framing misses the real distinction. NBA, NFL, and MLB daily fantasy are fundamentally different mathematical problems. Each sport imposes a different structure on randomness, correlation, and optimization. If you try to use the same mental model across all three, you end up misunderstanding at least two of them.

What follows is not strategy advice in the usual sense. It is a description of the underlying structure each sport forces on any serious model.

1) NBA

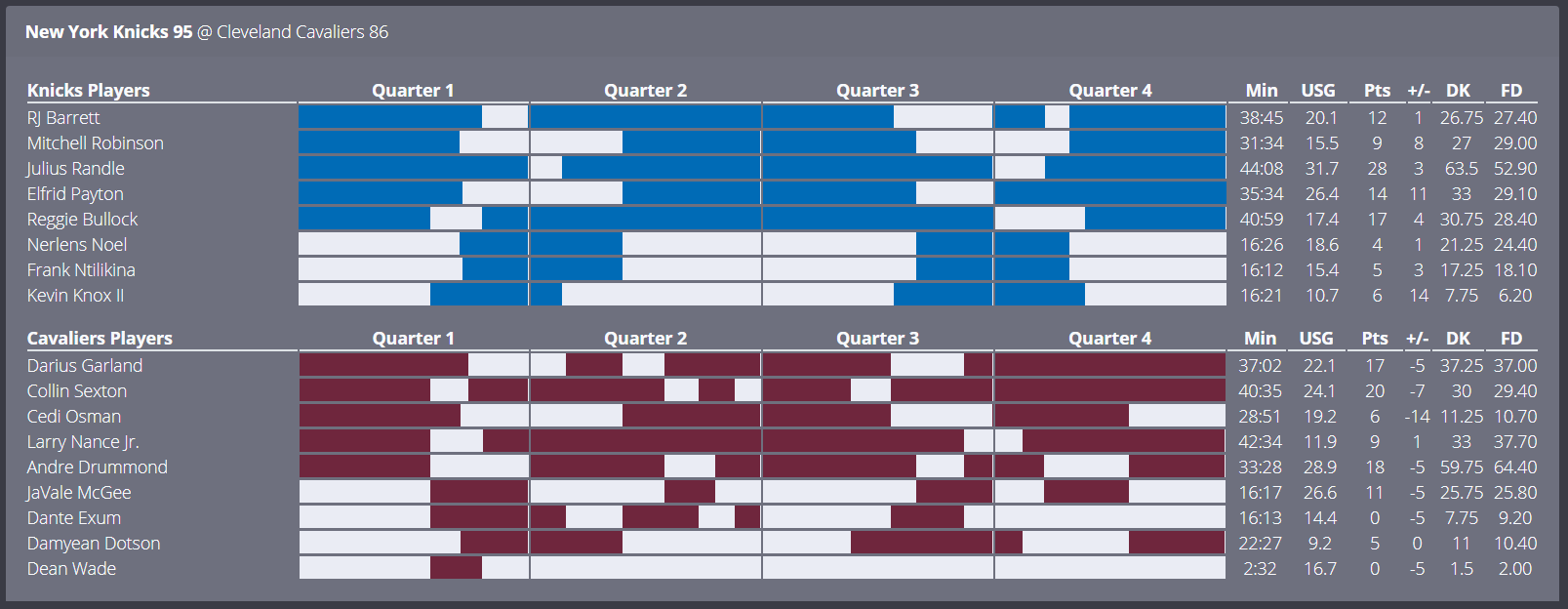

Basketball is the most forgiving sport mathematically. Scoring events are frequent and additive. A player’s fantasy output is the result of dozens of small contributions spread over minutes played: points, rebounds, assists, steals, blocks. This creates smooth distributions with relatively low variance compared to other sports.

The dominant variable is minutes. Usage matters, but usage is constrained by minutes. Rotations, injuries, and coaching decisions shape the distribution far more than matchup narratives. Because the signal is dense, linear or near-linear models perform well, and Monte Carlo simulation produces stable, interpretable distributions.

From a modeling perspective, NBA DFS is a constrained resource allocation problem under uncertainty about playing time. Correlations between players exist, but they are weak enough that independence assumptions are often acceptable approximations. Optimization behaves well. Small projection errors rarely destroy an entire lineup.

This is why NBA DFS feels “solvable.” The structure cooperates.

2) NFL

Football is the opposite. Scoring events are rare and discrete. Touchdowns dominate outcomes, and a single play can swing an entire slate. The sample size is brutally small. One game per week means uncertainty never averages out.

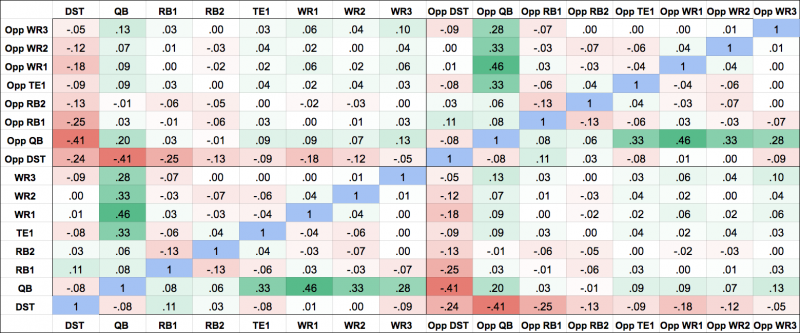

More importantly, NFL fantasy points are not independently generated. If a quarterback has a ceiling game, that production must flow through receivers or tight ends. If one team scores quickly, the opposing offense is forced into a different play-calling regime. Correlation is not a modeling detail. It is structural.

This breaks naive approaches. Modeling each player as an independent random variable produces lineups that look reasonable on paper and fail in practice. The correct place to introduce randomness is not at the player level, but at the level of games and teams. Game script, pass rate, and offensive efficiency are shared latent variables that induce correlation downstream.

NFL DFS is not about estimating expected values accurately. It is about constructing coherent scenarios and betting on joint outcomes. The optimizer should discover stacks naturally because the simulated worlds make them inevitable.

Football DFS is best understood as scenario-based stochastic optimization.

3) MLB

![]()

Baseball pushes variance to an extreme. Most plate appearances produce zero fantasy points. Home runs and extra-base hits dominate scoring, and they occur infrequently. Pitchers, meanwhile, contribute a disproportionate share of lineup variance and can single-handedly ruin or win a slate.

At the individual level, hitter projections are almost meaningless. The noise overwhelms the signal. This forces correlation back into the picture through stacking, but not in the same structural way as football. In baseball, stacks are less about shared opportunity and more about amplifying exposure to rare, high-impact events.

The distributions involved are heavy-tailed. Monte Carlo simulation still applies, but interpretation becomes subtle. You are not optimizing for typical outcomes. You are positioning yourself in the extreme right tail of the distribution and accepting that most lineups will fail.

Baseball DFS is not prediction. It is controlled exposure to variance.

One framework, three different uses

The same high-level framework can be applied to all three sports: simulate outcomes, then optimize lineups within each simulated world. What changes is where randomness lives and how it propagates.

In basketball, randomness lives at the player-minute level and averages out.

In football, randomness lives at the game and team level and induces correlation.

In baseball, randomness dominates everything and forces a focus on tail behavior.

There is no universal DFS model. There is only respect for structure.

Trying to force NBA-style projection thinking onto NFL, or NFL-style stacking logic onto NBA, is a category error. Each sport teaches a different lesson about uncertainty, dependence, and decision-making under constraints.

That, more than salaries or scoring rules, is what separates them.

No comments:

Post a Comment